Western culture considers the universe separate from man, so life is perceived as a “war” between opposites (light against darkness, life against death, good against evil, beautiful against ugly, etc.); this vision implies a sort of idealism to cultivate the former, considered positive for our culture, and get rid of its opposite, considered negative.

For TAOISM this is not understandable because it would be like wanting the electric current from the positive pole without having the negative pole, i.e. the polarities are different aspects of the same system and the disappearance of one polarity implies the disappearance of the other.

- – According to Tao “the only constant of reality is change, mutation” and he conceives the universe formed by KI energy ( see art. 50°), which is neither substance nor spirit but a “vital breath” that gives life and form to every kind of reality, both physical and spiritual. The Taoism accepts the laws of Nature for which there is always an alternation between the two polarities: day follows night, cold follows heat, death follows life, everything is created, then destroys itself and then regenerates itself.

- Taoism explains the structure of the universe and the physical and moral constitution of the individual with the interaction of two opposing but complementary forces which it calls YANG and YIN (yō and in, in Japanese), governing the creation and the transformation of the cosmos.

-

-

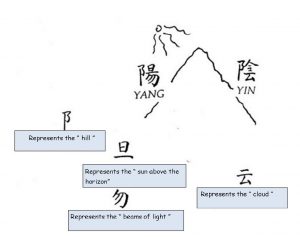

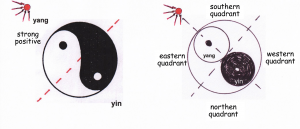

The yang ideogram indicates the sunny side of the hill, the yin ideogram indicates the side in the shade.

Being yang or yin is not an intrinsic quality but expresses the relationship between two entities: in this case the two sides of the hill.

- Consequently, the following pairs are classified:

- yang light hot dry rigid resistant strong heavy male positive

- yin cold shadow wet soft compliant weak light female negative

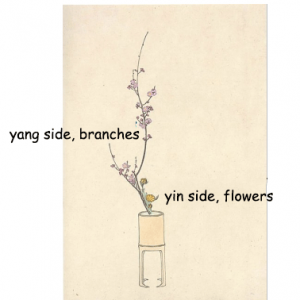

- The adjectives mentioned above are/were often used in ikebana and are equivalent to each other: for example, to define a strong or heavy, male, positive branch compared to a flower is to say that the branch is yang compared to the yin flower.

These adjectives are used to define some relative characteristics such as:

the side of the plant that grows in the sun is said to be positive while the one that grows in shade is said to be negative.

- Consequently, the following pairs are classified:

-

- As far as the leaves are concerned:Positive side is Yang, dark, facing the sun. Negative side is Yin, pale, grows in shade towards the ground. In leaves the yang side is darker than the yin side

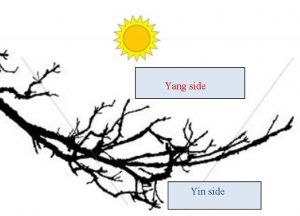

About the branches:

- As far as the leaves are concerned:Positive side is Yang, dark, facing the sun. Negative side is Yin, pale, grows in shade towards the ground. In leaves the yang side is darker than the yin side

-

the positive side or Yang, grows towards the sun and is frequently the concave part and darker in colour while the side grown in the shade, called negative or Yin, is convex and paler. If the branch has leaves and/or flowers, it is easier to tell which side is Yang/sun facing simply looking carefully at them.

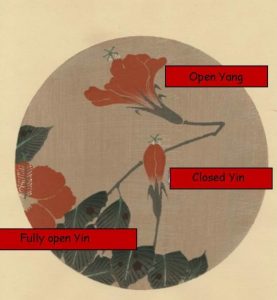

the flower when in bud is considered weak-Yin-female, the open strong-Yang-male, while the very open, older, flower is again considered weak-Yin-female

Western ladies, when they read this weak-female-negative association, full of negative connotations compared to strong-masculine-positive, might think that Taoism is chauvinist. This is not so because the terms do not have the same value that Westerners give them and Taoism considers yin-feminine weaker more important than yang-masculine strong because the former allows change, an indispensable factor for the continuity of life. Remember that for Taoism “the only constant is change”.

If we consider a branch with leaves and/or flowers, the wood is Yang compared to the leaves/flowers; they are both considered Yin compared to wood: in general, to obtain a balance between Yang and Yin, the ikebanist must prune it so that the wood/Yang is clearly visible. This is necessary because in nature generally it is covered by too many Yin leaves/flowers.

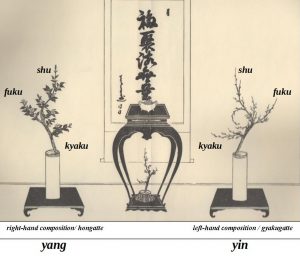

- The hongatte/right-hand composition is considered strong-yang compared to the gyakugatte/ left-hand composition which is considered weak-yin. see art. 16°Above two Soka with the three main elements indicated, for simplicity, with the names used by the Ohara school.Before westernisation imposed its own botanical categorisation, the classification of plants was based on the yang-yin system:1-material KI-MONO (KI = tree, MONO = thing) which is yang and includes branches of trees and shrubs, i.e. everything that is wood. 2-material KUSA-MONO (Kusa = grass) which is yin and includes flowers, herbs, leaves.

3-material TSUYO-MONO (TSUYO = common to…) which can be yin or yang depending on its role and on the plant to which it is associated. For example bamboo, wisteria, peony, spirea, hydrangea can be yang if used in the shu-fuku group associated with flowers in the kyaku group but can became yin if utilized in the kyaku group associated with Ki plants in the shu-fuku group.

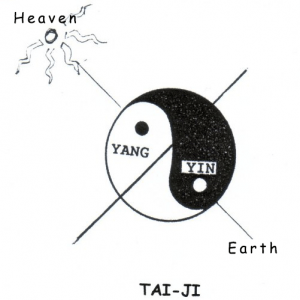

The yang/yin theory is symbolized by Tai-ji, a circle representing “the whole” divided into two equivalent parts, the yang part on the heaven/sunny side and the yin part on the earth/shady side.

In the drawing the two parts are divided by two imaginary black lines: a darker one divides the yang part of the circle from the yin part, the other is perpendicular to the first and joins the maximum-yang point, ideal point of maximum light and ideal position of the sun, with the maximum-yin, point of maximum darkness.

see art. 15th on the symbolic origin of ikebana in which the construction of Tai-ji is explained.

Please note:

The yang part of the circle is not all white but the semicircle, above the imaginary black line, on the side of the sun and includes the “head” of the white part plus the “tail” of the black part while the yin part is the semicircle on the earth side, below the imaginary black line, including the “head” of the black part and the “tail” of the white part. The imaginary line separating the yang part from the yin is inclined 45° from the horizontal. see art. 15°

Tai-ji symbol highlights:

1- although opposites, the yang and yin forces are complementary

2- nothing is completely yang or yin: the yang side contains a black seed of yin and the yin side contains a white seed of yang.

3- yang changes into yin and vice versa.

-

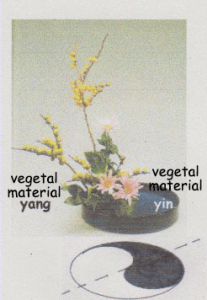

The styles of ikebana born before the westernization, represent the Tai-ji with the vegetal material i.e. the composition is constituted by yang plants (wood) in the part on our left of the composition (if this is hongatte) and by yin plants (herb-flower-leaves) in the part on our right.

-

see art. 15: on the construction of Tai-ji

- This subdivision is visible in Rikka and Shōka/Seika and has also survived in the styles (kata, KUN reading, kei, ON reading) of the Ohara school where the shu-fuku group is yang, wood material, while the kyaku group is yin, flower material, as in the above figure of a Moribana Chokuritsu style.

-

- Generally speaking, the material used in the shu-fuku group must be “stronger”/yang than the material used in the kyaku group, which is composed of “weak”/yin plants compared to the plants utilized in the shu-fuku group.

-

- During the Edo period, abandoning only in very special cases the Taoist symbology described above, Rikka and Shōka/Seika also began to be composed with only one species of plants, for example pine, maple, or with some specific flowers such as irises, lotus, chrysanthemums and narcissus. see art.70°

From the end of the 1800s onwards, ikebana also began to be composed with any type of herbaceous flower, no longer applying the rules of yin/yang which showed the balance of the universe in ikebana through the presence of yang/branches and yin/flowers.

- After the 1930s, as the influence of Western culture increased, many schools partially abandoned this symbolism in their new ikebana creations. The Ohara School has kept it in styles like Chokuritsu-kei, Keisha-kei, Kansui-kei and Kasui-kei while this symbolism has been abandoned (but occasionally reappears) in the Forms of ikebana created after the 1930s and codified after the Curriculum revision which took place in 2000 and 2020. see art. 67°

If the ikebanist wants to be coherent with the rules of the past, when using only herbaceous flowers he will remember that the shu-fuku group must be yang/”stronger” than the kyaku group and he will express this knowledge of the history/culture of ikebana using “strong”/yang colours or shapes in the flowers of the shu-fuku group compared to the “weak”/yin flowers of the kyaku group.

Interesting this composition of the Ohara school in which the concept “strong”/yang and “weak”/yin is not expressed according to the traditional rules using yang/wood for the main element and yin/flower for the secondary element. Here instead appears the use of an herbaceous/yin plant, but with leaves that are very large and dark green, which appears “strong” in comparison to the small, light green leaves of the maple branch/yang that appears “weak”, considering the volumes and colours.

- It is important for the ikebanist to keep in mind which is the yang/positive part of each individual plant because in all styles of the Ohara school there is the rule that “all plants look – show their positive side/yang- primarily towards the sun (positioned roughly above the head of the ikebanist who os arranging ) and secondly towards the main shu element”.

-