Plants, in their whole and in their single parts, grow in nature in a harmonious way with respect to the plants that surround them. Once they have been picked and detached “from the natural harmony” in which they have grown and are arranged in a container, it is only through the compositional rules of ikebana that harmony between the plants is restored.

This happens because these rules derive from religion-philosophies (Shintoism, Buddhism and Zen Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism) in which Man and Nature are part of the same entity (unlike Christianity which sees them separated) and therefore “governed” by the same principles; moreover, these rules (as in all Japanese Traditional Arts) have been “distilled” passing from one generation of Ikebanist masters to the other from the 15th century to the present day.

As happen with the grammatical rules, for those who learn a foreign language, which must be learned and “pedantically” applied by the beginner and then forgotten by those who speak the language fluently because they have acquired them, the rules of ikebana are not an end in themselves but serve to understand the guiding principles governing the relationships between the individual plants, the container, the place where the composition is placed.

THE DISPOSITION OF VEGETABLE ELEMENTS IN IKEBANA HAS ALWAYS REPRESENTED SYMBOLICALLY THE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF ITS CREATORS AND ITS CUSTOMERS, THEIR RELIGIOUS AND PHILOSOPHICAL BELIEFS. AND EVEN THOUGH THESE SYMBOLS HAVE LOST THEIR MEANING OVE TIME, THE BASIC STRUCTURE OF THE IKEBANA BASED ON THESE SYMBOLS HAS STAYED PRACTICALLY UNCHANGED TO THIS DAY.

|

The compositions since the 15th century (the period in which ikebana appeared) until the beginning of the Edo period were symbolic constructions that used plants to represent philosophical-religious concepts. These compositions expressed the harmony of the universe by referring not only to Shintoist and Buddhist symbolism but also to the concept of yin/yang. see art. 2 |

|

in fact:

|

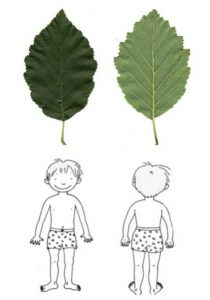

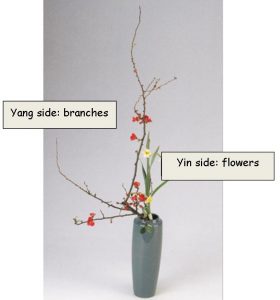

° of the leaves, branches and flowers is considered: – Yang the side that grows towards the sun (hi-omote) and – Yin the side, that grows towards the ground (hi-ura) hi=sun omote=face/side ura= opposite, below |

Front/Yang/Positive Back/Yin/Negative |

° of the whole composition one side was considered yang (containing yang plants: ki-mono, ki=wood) and the other one was considered the yin side (containing yin plants: kusa-mono, kusa=grass) see art. 15°: Ikebana’s symbolic origins

° the composition was composed by an odd number of elements (odd numbers are preferred because they are considered yang) with the only exception of number two which, although yin, like all even numbers, is used because it is considered the sum of yang + yin. see art. 62°

It was only during the Edo period (1603-1868 ), that both the cosmic and mystical vision of life and the sacred perception of nature, characteristic of previous eras, began to decline. At the same time a process of secularization of the arts in general, including Ikebana, takes place: the symbology on which the creation of the compositional rules of ikebana was based is considered outdated and, little by little, is partially forgotten: most of these compositional rules based on religious-philosophical symbols continue to be applied without knowing their symbolic origin.

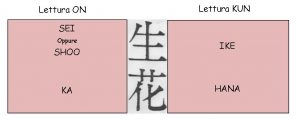

The arrangements are now perceived in a different way and, consequently, they are identified with a new reading of the kanji. While at the beginning of the Edo period, they were read in On-reading shō-ka/sei-ka now they are read, in Kun-reading, ike-bana, highlighting the verb ikeru=giving life, i.e. plants are no longer seen for their symbolism but express themselves as living beings. see art. 50°, about On-reading and Kun-reading and 54°, kanji reading and the evolution of ikebana

Despite this change in the overall view of compositions, the basic rules of composition remain those of the Rikka, even if simplified.

Still at the beginning of 1800 in the text “Enshū sōka ikō kadenshō” (oral transmission of the ikebana of the Enshū school), anonymous dated 1801, is peremptorily asserted:

-if in a composition you don’t find the principles of yin/yang, this is not an ikebana.

In Japan, religious and philosophical syncretism has always been practised, i.e. there has never been the need to choose one religion or philosophy while rejecting the others; from every religion or philosophy, people have always chosen what seemed most suitable or useful depending on the circumstances, be it in private or public life or for rites of passage such as birth, marriage, funeral.

Also ikebana reflects this syncretism because in its construction the symbols of different religions and philosophies are easily recognizable: the choice of plants and their association, their ideal position in the composition and their direction, the measures, all are based on the symbols of Taoism, Shintoism, Buddhism, neo-Confucianism and on magical-religious practices such as feng-shui.