The origin of ikebana according to tradition was written in the second half of the 1700s by the Ikenobō, and relates the birth of ikebana with historical figures who really lived but whose involvement with ikebana is historically impossible.

In the Azuka period (552-710 A.D.) Empress Suiko was elected. She was the first woman-tennō of the eight empresses who reigned in Japan and she ruled from 593 to 628 A.D. see article no. 111

|

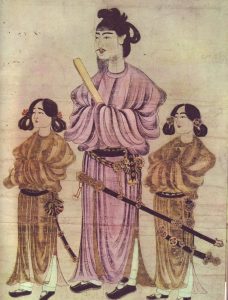

She appointed as Regent her nephew Prince Umayado (born 574 and died 622), known by the posthumous name of Shotoku Taishi = shining prince.

He was the second son of Emperor Yōmei, (in the two drawings together with two dignitaries drawn smaller than he to highlight his importance was). He was an important figure who supported the introduction of Buddhism at the imperial court and, according to tradition, wrote the first Japanese Constitution of 17 articles. He also introduced the use of the Chinese calendar used in Japan, with a few adaptations, until 1873 when the Gregorian calendar was introduced. |

|

Looking at the garments and hairstyles, the Chinese influence on the Japanese Imperial Court at that time is evident.

|

|

|

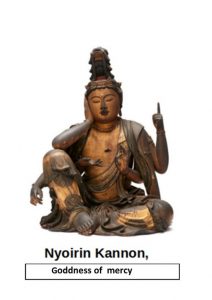

Tradition has it that Shotoku Taishi, an ardent Buddhist, always carried a statuette of the goddess of compassion, Kannon. During one of his journeys, being very hot, he stopped to cool off by a pond but when he wanted to put his clothes on and leave, the statue had become very heavy. He therefore spent the night close to the pond and dreamt that Kannon wished a temple to be built there in her honour. Taishi had it built and, being hexagonal in shape, over the years it was called Rokkakudō = hexagonal temple. |

|

According to the legend, the Rokkakudō was built in an area that was to be chosen for the new capital, the construction of which began around 794 and became the seat of the imperial court. The new capital was called Heian-kyō, today’s Kyoto. Historians agree that the Rokkakudō was actually built in the capital more than 170 years after Taishi’s death -which occurred in 622-, when the new capital already existed The Rokkakudō is the historical seat of the Ikenobō School. Rokkakudō |

|

Japanese banknotes showing both Shotoku Taishi and the Rokkakudō

At the head of two embassies to China in 607 and 608 was ONO NO IMOKO, nephew of the emperor Bidatsu (538-585) and cousin of Taishi. His return from the second embassy is historically documented but this is the last historical information about him: from his return from China onwards, he is no longer mentioned in any source

The Japanese imperial message, brought by Imoko to the Chinese Emperor Yang in the first embassy, started with:

“the son of Heaven where the sun rises (i.e. Japan) to the son of Heaven where the sun sets (i.e. China)………”

This message probably annoyed the latter because it equate the two emperors, while the Chinese imperial court considered the Japanese to be an insignificant and barbaric people.

When Ono no Imoko returned from the second embassy, Taishi was dead and at this point tradition states: Ono no Imoko took his vows and retired to Rokkakudō, becoming its abbot and taking the name of the Buddhist monk SENMU.

It is said that he began to create flower offerings to the altar of Buddha the way he had learned to do in China.Tradition states that he lived in a hut adjacent to the Rokkakudō located by the pond where Shotoku Taishi had cooled off. Hence the origin of the name Ike no bō (=hut by the pond).

Rokkakudō, Kyoto

According to tradition, the abbots who followed him at the head of the Rokkakudō continued to occupy themselves and develop this art, which in the Edo period was called ikebana.

From the second abbot onwards, as monks, they assumed names that all began with SEN, a custom that has survived to this day.

Historically, the name (Senkei or Senei) Ikenobō first appears in a diary of the Kyoto Buddhist monk, Hekizan Nichiroku, dated 25 February 1462, in which it is said that many people saw compositions in a golden vase performed by the monk Senei Ikenobō.

From the 608, the historical date on which Ono no Imoko returned from the second embassy (and retired, according to legend, to Rokkakudō, taking the name Senmu) until 1462, the year when the name ikenobō first appeared in the diaries, this name has never been mentioned in any other historical source that has come down to us.

With the aim of increasing or strengthening the prestige and legitimacy of the school, the Ikenobō, as well as associating the birth of their name with Shotoku Taishi, associated Senkei Ikenobō with the Ashikaga shoguns saying that he was in the service of Yoshimasa, the eighth shogun, and that in 1479 the latter named him: “Dai Nippon Kado no Iemoto” (he who originated ikebana).

Thus demonstrating Yoshimasa’s alleged preference for the Tatebana created by Senkei over those created by the dōbōshū of the Ji sect.

The dōbōshu were secular-monks in his employ, who first created the Tatebana; the association of Senkei Ikenobo with the shogun Yoshimasa is considered by historians to be untrue.

Although texts written on Tatebana appear as early as the 14th century (e.g. Sasaki Dōyo 1306-1373) and in various journals there is mention of “arranging/putting upright” (TATERU ) flowers, as for example in a record dated 20 April 1476. In this it is said that Yoshimasa, on the occasion of his visit to the Imperial Palace, asked his dōbōshū Ryūami to ” put up rights” (TATERU) of peonies. The same action is also described on other pages with other flowers.

Tradition links the birth of Ikebana only to the Ikenobō School, but this tradition was written by the Ikenobō themselves in the Edo period at the request of the Tokugawa shoguns.

The dōbōshū see article 33 , the first “creators” and codifiers of the rules of the Tatebana, disappeared with the fall of the Ashikaga and the Ikenobō, now the only ones dealing with this art, began the hegemony in the field of ikebana that would last until the middle of the Edo period, when the other schools were born, all derived from the Ikenobō school.