references at the bottom of the page

The aim of this website is to arouse the curiosity of ikebanists by giving them a vision of Ikebana where its form is not separated from its meaning and to encourage the reader to go deeper into the themes presented here. Nowadays there is a general tendency in Western art to appreciate the form for itself. The different compositions of ikebana are admired for the beauty of the plants used, forgetting that their position and direction, their choice and association, their size and their orientation, their thinning, all have a meaning because they are based on compositional rules that symbolize Shintoism, Taoism, classical and Zen Buddhism, feng-shui and neo-Confucianism.

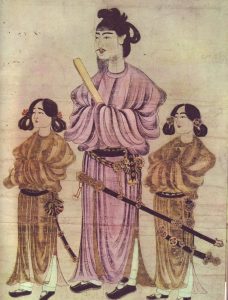

Since the concept of divinity in Shintoism is found in natural elements, this allowed it to coexist with other value systems that have penetrated Japan from abroad: in the 7th century, Prince Shotoku Taishi, regent and nephew of Empress Suiko, said: “Shintoism is the trunk, Buddhism is the branches and Confucianism the leaves”.

Japanese culture has always shown a sort of syncretism by accepting the beneficial elements of different, and at times contrasting, religious value systems, making only the most convenient aspects of what was im The religious syncretism, is a characteristic feature of Japanese culture, we find it in ikebana because its compositional rules are based on symbols of various religions.

Only by knowing the history (and how it has influenced in the shaping of collective ways of thinking and in making some values something absolute) can we grasp the meanings of traditional Japanese arts in general and of ikebana in particular.

Otherwise knowledge will be shallow and limited to its exterior appearance.

Considering that most blogs or websites deal with the technique but not with the culture that underlies the understanding of an ikebana, the idea behind this blog is to give explanations that allow a deeper look at the many forms of ikebana, that is, an understanding of its structures and meanings. See art. 25°.

This site has been created to be consulted every time the ikebanist encounters a new theme that is little known to him/her or wants to deepen a theme that is known to him/her; by inserting words to be searched for in the white box at the top left, you can find all the essays concerning the theme searched for.

Disclaimer

The author has no commercial interest in this blog. Texts and images are personal or extracted from Internet; if their publication violates the copyright, the owner can communicate this by email and they will be immediately deleted.

Some references:

IKEBANA

Articles and seminar notes.

L’ikebana, filosofia, religione e teoria dei fiori

Ikebana pratico, together with Masanobu Kudō

Ikebana fiori viventi

Ikebana, quando i fiori diventano arte

Ikebana, l’arte meravigliosa di disporre i fiori

Corso di Ikebana, l’arte di disporre i fiori

By Jenny Banti-Pereira

Flower Arrangement, Art of Japan

By Mary Cokely Wood

The Mastery of Japanese Flower Arrangement

By Koshu Tsujii

The Masters`Book of Ikebana

By Sen`ei Ikenobo, Houn Ohara, Sofu Teshigahara

The Art of Japanese Flower Arrangement

The Way of Japanese Flower Arrangement

By A. Koehn

The Art of Flower Arrangement in Japan

By A. L. Sadler

The Theory of Japanese Flower Arrangements

The Flower of Japan and The Art of Floral Arrangement

By J. Conder

The Flower Art of Japan

Japanese Flower Arrangement

By Mary Averill

Japanese Floral Art: Symbolism, Cult and Practice

By Rachel Carr

Flower Arrangement: The Ikebana Way

By Minobu Ohi, Senei Ikenobō, Houn Ohara, Sofu Teshigahara

Paysage: un art, une école, un espace

L’ikebana

By Martine Clément

The Joy of Ikenobo Ikebana 2011

Ikenobo Ikebana Basic Guide

Ikebana-related themes

Estetica del vuoto

Dieci lezioni sul buddhismo

Yohaku

By Pasqualotto Giangiorgio

L’ideale della Via, Samurai, monaci e poeti nel Giappone medioevale

La cultura del Tè in Giappone

By Aldo Tollini

Il pensiero giapponese classico

By Massimo Raveri

Sources of Japanese Tradition, volume 1 and 2

By Theodore de Bary, D. Keene, George Tanabe, Paul Varley

Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art

By Ernest F. Fenollosa

Yin and Yang, l’armonia taoista degli opposti

By J. C. Cooper

Il Tao: la via dell’acqua che scorre

By Alan W. Watts

The Culture of Civil War in Kyoto

By Mary E. Berry

The World turned upside down

By Pierre F. Souyri

The Ideals of the East

By Akuzo Okakura

Samurai, i guerrieri dell’assoluto

By B. Marillier

Lo stile eroico, l’eroismo in Giappone

By Junyu Kitayama

La maschera del samurai

By Aude Fieschi

Zen and the fine Arts

By Shin’ichi Hisamatsu

Lo zen e l’arte di tirare di spada

By R. Kammer

The Japanese Arts and Self-cultivation

By Robert Carter

Bushido, l’anima del Giappone

By Inazō Nitobe

The Samurai and the sacred

By Sthephen Turnbull

KO-GI-KI, libro base dello shintoismo giapponese

By Mario Marega

Lo spirito delle arti marziali

By Dave Lowry

Lo Zen e la via della spada

By Winston L. King

Kata

By Kenji Tokitsu

La via del tiro con l’arco

By Paolo Villa

The Zen Arts

By Rupert Cox

Japanese Tea Culture, art, history and practice

Handmade Culture, Raku Potters, Patrons, and Tea Practitioners in Japan

By Morgan Pitelka

Rediscovering Rikyu and the Beginnings of the japaneseTea Ceremony

By Herbert Plutschow

An introduction to japanese tea ritual

By Jennifer L. Anderson

Tea culture of japan

By Sadako Ohki

Zen in the Art of Tea Ceremony

By Horst Hammitzsch

Lo spirito del Giappone

By Leonardo Vittorio Arena

Gli insegnamenti della pittura del giardino grande come un granello di senape

Edited by Mai-Mai Sze

About Japanese aesthetics

By Donald Richie

La tradizione estetica giapponese

Dalla città ideale alla città virtuale Estetica dello spazio urbano in Giappone e in Cina

By Laura Ricca

L’estetica giapponese moderna

By Marcello Ghilardi

Giappone, la strategia dell’invisibile

By Michel Random

I fiori del vuoto

By Giuseppe Jisō Forzani

The Origin of Japan’s Medioeval Word

Cultural Life of the Warrior Elite in the Fourteenth Century (Chapter 9)

edited by J.P. Mass

Japan in the Muromachi Age

- by J.W. Hall and Toyoda Takeshi Ashikaga

Yoshimitsu and the World of Kytayama (Chapter 12) By H. Paul Varley

Emperor and Aritocracy in Japan 1467-1680

By Lee Butler

The Japanese Way of the Flower: Ikebana as Moving Meditation

By H. E. Davey

Dizionari delle religioni: Taoismo

By Ester Bianchi

La mente giapponese

By Roger J. Davies e Osamu Ikeno

Themes in the History of Japanese Garden Art

Wybe Kuitert

Daimyo Gardens

By Shirahata Yozaburo

Book of Tea

By Kakuzo Okakura

TEA OF THE SAGES: The Art of Sencha

By Patricia J. Graham

San Sen Sou Moku, il giardino giapponese nella tradizione

By Sachimine Masui, Beatrice Testini

L’universo nel recinto, I fondamenti dell’arte dei giardini e dell’estetica tradizionale giapponese, І e 2

By Paola Di Felice

The Shogun’s City, a History of Tokyo

By Noël Nouët

Kaempfer’s Japan, Tokugawa Culture Observed edited, translated by B. M.

By Bordart-Bailey

The Origin of Japan’s Medioeval World

Courtiers, Clerics, Warriors and Peasants in the Fourteenth Century

Edited by Jeffry P. Mass

FENG SHUI

By Ernest Eitel

Modern Reader on the Chinese Classics of FLOWER ARRANGEMENT

By Zhang Qiande and Yuan Hongdao

Compiled by Li Xia

Cultivating Femininity Women and tea Culture in Edo and Meiji Japan

By Rebecca Corbett

STORIA DEI SAMURAI E DEL BUJUTSU, nascita ed evoluzione dei bushi e delle loro arti nel Giappone feudale

By Roberto Granati

Storia del Giappone

By Kenneth Henshall

Senno (Ikenobō), on the Art of Flower Arrangement ( Chapter 5 ) in

Literary and Art Theories in Japan

By Makoto Ueda

The I Ching in Tokugawa Thought and Culture

By Wai-ming Ng

KAZARI Decoration and Display in Japan 15th-19th Centuries, 2002

edited by Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere

KAZARI L’arte di esporre il BONSAI e il SUISEKI, 2016

By Edoardo Rossi

Warlords, Artists and Commoners,

Japan in the XVI Century

edited by George Elison, Bardwell L. Smith

The politics of reclusion, painting and power in Momoyama Japan

By KENDALL H. BROWN

Kire: il bello in giappone

By RYOSUKE OHASHI

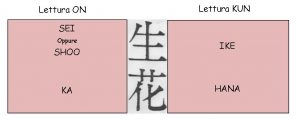

KA ( ON reading ), hana ( KUN reading) = “flower

KA ( ON reading ), hana ( KUN reading) = “flower KA ( ON reading ) and uta ( KUN reading) = poetry

KA ( ON reading ) and uta ( KUN reading) = poetry

shi the number four

shi the number four is shi, meaning death

is shi, meaning death

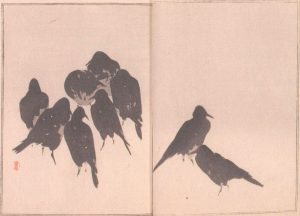

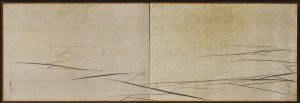

Ice with cracks, 1780

Ice with cracks, 1780 Ducks on the beach

Ducks on the beach