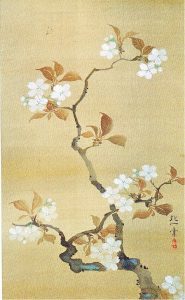

Historical records show that ikebana, with a rule-based structure, was born during the Muromachi period (1333-1568) thanks to the patronage of the Ashikaga shoguns.

The third shogun Yoshimitsu, (1358-1408) promoted those arts that we know as ‘traditional Japanese

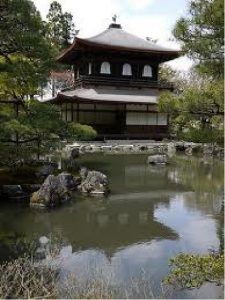

When he retired as shogun, he built and settled in the Golden Pavilion in Kitayama = yama/kyta hill/north. Suburb of Kyoto.

Regarding the period in which ikebana was born we have many traditional stories from the Ikenobo School. On the other hand, there is poor historical documentation on the subject because present-day historians, who still know little about ikebana, have so far dealt with the subject in a limited way

One of the characteristics of this period is the term basara (ostentation, excess, extravagance) and the beginning of ikebana starts with those basara samurai such as Sasaki Dōyo (1306-1373), Shugo in the service of the first shogun Ashikaga Takauji, who recounted in his diaries the refined entertainments of the warrior aristocracy. During these events, people exhibited the Tatebana, competed in quoting poetry or guessing the names of the perfumes burned in the incense burners. They also competed in guessing the origin of the various teas that were served along with sake and delicious food. Sasaki also wrote a book on Tatebana etiquette which is referred to as Tatebana Kuden Daiji (nowadays the kanji tatebana is read rikka). See Art. 54

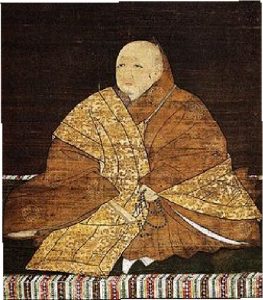

His nephew, the 8th shogun, Yoshimasa (1443-1473) took these arts to their highest level and made them “typically Japanese”. When he retired as shogun, he too had a residence built: the Silver Pavilion, in the area of Kyoto called Higashiyama = Higashi hill/east

The importance of these two shoguns, compared to the other 15 Ashikaga shoguns that followed one another in the Muromachi period, is such that the culture of this entire period is divided into only two parts that take their name from their residences, namely:

Kitayama culture, from 1333 to 1450, from the residence of Yoshimitsu.

Higashiyama culture, from 1450 to 1568, from the residence of Yoshimasa

In the military hierarchy of the time, it was not possible for a soldier below the shogun to be more educated than of the shogun himself in any field, so the Ashikaga had instead employed the dōbōshῡ (attendants).

These were mostly Buddhist monks of humble origins, who took vows but did not enter a monastery permanently and, even though they were monks, continued the way of life they had before withdrawing from public life (for example, if they were married, they continued to live in their house with their wife and children). They were secular monks and, although they had their heads shaved like other monks, were dressed in bright colours (whereas Buddhist monks were in black), could carry swords inside the shogunal palace and were the cultivated men and cultural leaders of the time.

At the beginning of the Ashikaga period, most of the dōbōshῡ belonged to the Ji sect, founded by the monk Ippen in the middle of the 1200s. When the sect was founded, they had various tasks: accompanying the Daimyō in battles with the responsibility of treating the wounded, reciting prayers for the dead, communicating deaths to the clans and delivering the armor of the deceased. They were characterized by a name ending in AMI, in honour of the Buddha Amida see, for details, article 33: ikebana and history.

In times of peace they had other tasks: entertaining the samurai with poetry competitions, tea and incense ceremonies, organizing invitations and looking after guests.

As time went by, the tasks of “cultural entertainment” took precedence over the others and they became the exclusive attendants of the Ashikaga shogun.

The dōbōshῡ were the cultured men of the time, arbiters of taste and aesthetic advisers to the shoguns: each of them was an expert in the various art forms of the time, either as a poet or as a connoisseur of perfumes or as a painter or as an ikebanist or as a garden builder or as a curator and restorer of the precious objects of the shogunal artistic collection (such as the famous “three Ami”, grandfather-father-son Noami, Geiami, Soami).

Their culture, sponsored by the Ashikaga, became the dominant one and this fact allowed the samurai class to emerge from its cultural position subordinate to the Imperial Court, the only source of culture until this historical period.

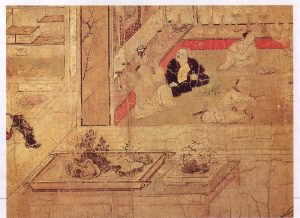

Some dōbōshῡ were in charge of cataloguing the Ashikaga’s private collections, the majority of which were of Chinese origin, from pottery to lacquerware, paintings and drawings, and their tasks included preparing the banquet halls for the shogun’s guests, decorating them with “rare Chinese pieces” (karamono kara=China mono=things) from the shogunal collection

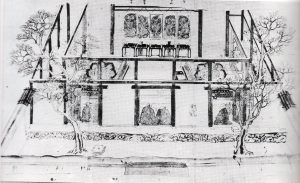

Painting showing the displayed some “karamono”, in which Chinese vases that do not yet contain any plants

Yoshimitsu’s passion for Chinese objects and the re-opening of the trade, inactive since the Heian period, with China to obtain them culminated in the fact that in 1403 he accepted to be a vassal of Yongle, third emperor of the Chinese Ming dynasty, who appointed him -king of Japan- probably because he did not know of the existence of an emperor

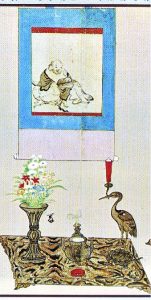

During the shogunate of the eighth Asikaga, Yoshimasa (1435-1490), receptions began to feature a triad of sacred paintings (kakemono) on the main wall where objects were displayed on shelves, The central kakemono always representing Buddha; at its feet was a small raised table (oshi-ita) with the “three sacred objects” (mitsugusoku): an incense burner, a candlestick and a vase with flowers (where the vase was much more important than the flowers).

This way of arranging the three or five kakemono had been done for a long time but only in a religious context: on the side, a drawing dated 1160 showing a chapel of the Shingon Buddhist sect, founded by Kukai (774-835) in which five kakemono are displayed with five small tables with incense burners in front of them. The dōbōshῡ brought this way of arranging the kakemono from a sacred place to the shogun’s secular residence.

It was from this practice, formalized in the second half of the 15th century under the patronage of the eighth shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, that ikebana with compositional rules began- The small table with the three sacred objects became the tokonoma and at the same time the vases with the flowers became more and more important and their vegetable content was more structured. From a single vase, there were now three vases.

Or five vases in more formal situations

As time went by, the incense burner and the candlestick lost their importance and were no longer placed in the tokonoma, leaving only the three vases whose vegetal content began to be structured according to the rules that still govern the construction of an ikebana today. In the beginning, the vases were important and were displayed for their beauty while the flowers played a secondary role; now it is the flowers that have taken on greater importance and the vases are chosen according to the plants: they are built specifically to contain the plants of the tatebana/rikka.

|

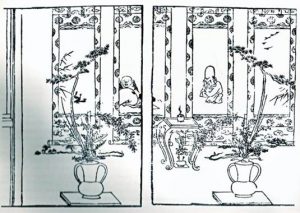

Right-hand composition/hongatte |

Left hand/gyakugatte composition |

As explained in the 5th article (Relationship between ikebana and environment), the definition of the “right-hand” (hongatte) and “left-hand” (gyakugatte) compositions is associated with their position in relationship to the central painting with Buddha in the tokonoma.

In this period there are many variations on the theme as can be seen from these drawings in which the importance/position of the three sacred objects varies.

As time went by, two more tatebana/rikka were added to the three sacred objects, forming what is referred to as “the five sacred objects” (gogusoku) up to even five tatebana/rikka, in very formal situations and in large tokonoma.

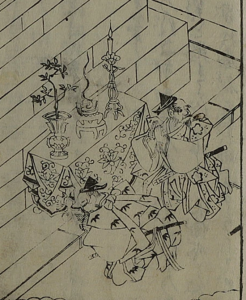

The importance of the “three or five sacred objects” (mitsu/go-gusoku) has remained in Japanese culture: for example we find them in this drawing entitled Formal arrangement of food for shoguns, daimyo, nobles and emperors dated 1630 in which the green incense burner is set back, the ikebana and the candlestick are central while in the foreground we see two small tables with large floral arrangements and at their sides two more candlesticks.

The earliest compositions were tatebana (hana=”flowers” tateru=erects, straight) and in a journal that has come down to us, dated 2nd April 1476, it is said that Yoshimasa ordered the doboshu Ryuami to “set straight” some peonies.

TATEBANA

As time went by, the incense burner and the candlestick lost their importance, took a back seat, and then disappeared altogether, leaving only the two side vases whose plant content began to be structured according to the rules that still govern the construction of an ikebana today.

In the beginning, the Chinese vases were very important and were displayed for their beauty, while the flowers played a secondary role; later on, it was the plants that became more important: the vases were chosen according to their function and were no longer chosen at random, but built specifically to contain the plants of the tatebana/rikka.

As explained in the 5th article (relation between ikebana and environment), the origin of the definition of the “right-hand” (hongatte) and “left-hand” (gyakugatte) compositions is associated with their position in relation to the central painting of Buddha in the tokonoma.

This ‘birth’ of ikebana took place gradually in the second half of the 1400s. Placing flowers in front of altars is a common practice in all religions, but putting mainly branches with few flowers, structured and with rules, only happened in Japan. Flower offerings to Buddha occur throughout the Buddhist world and from the 16th century, when Buddhism was introduced in Japan, to the mid-1500s (i.e. for about 900 years) there are no historical sources describing flowers or branches arranged in vases with rules. The first “structured” forms of ikebana (tatebana) appeared only in the mid-1400s, at the same time as the appearance of the tokonoma: therefore ikebana was born in a “secular” context in the homes of the shogun and the warrior nobility, where the kakemono with Buddha was not used as an altar in front of which people actually prayed, but only to give importance to the objects on display.

Following the Japanese practice of religious syncretism, the Ashikaga shoguns personally adhered to various Buddhist sects in addition to Shintoism, without being bound to any in particular, and the various monks in their service were chosen not so much for the Buddhist sect they followed as for their skill in the various artistic fields of interest to the shogun.

From the union of the oshi-ita, raised tables on which the three sacred objects (mitsugusoku) are placed, the tokonoma was born at the same time as the ikebana it contained.

With the exception of the rikkas made up on the side of the Great Buddha of Nara by Hideyoshi (which after all were done in honour of himself and not of the Buddha – see the painting on the side with the proportions of the two Rikkas taller than the head of the statue – there are no descriptions that speak of ikebana on the altars of any Buddhist sect/current; even the Ikenobo never put ikebana in the Rokkakudo but their exhibitions always took place in other buildings.

Therefore historically demonstrated ikebana appeared and became an art mainly in the secular sphere of decoration and arrangement (kazari) of the precious objects (karamono) of the Ashikaga shoguns.